At 7 pm on November 27th, 15 other displaced Americans, 6 Australians and 5 Nepalis arrived at my door, their hands full of pies and casseroles, roast chickens (no turkey in Nepal) and more-than-we-could-eat potatoes.

We'd decided to have Thanksgiving at my house for two reasons: the toaster oven and the back up generator (that only sometimes works).

It was a hell of a night. And left a lot to be thankful for.

Here are some highlights:

Sunday, November 30, 2008

Saturday, November 29, 2008

Morning-time

My dad recently visited. (That’s for another story. SO GREAT.)

His visit made me realize that I’ve not shared much of my daily routine. Haven't shared the little things: The smell of my alley. The vegetable lady (toothless, nose-ring), the fruit guy (smiley, calls me “didi” meaning “older sister”) and the corner shop lady who I buy walnuts and flour from (tight-lipped, wearer of tennis-ball-sized hoop earrings). How these days I prepare a hot water bottle before bed each night to keep my toes warm.

My routine will change soon. I might be moving in with a Nepali family, or at least share most dinners with them.

But here is my morning routine as it stands now.

It feels boring. But it’s real.

‘Eeeeeh-eeeeeh-eeeeeh!’ The high-pitched beep of my alarm jolts me awake. I groan.

I reach for the ledge behind me, knocking over my book and headlamp before I grasp my alarm clock. I click it off, stretch my arms up and squint open my eyes. The sun is bright in my room.

I pull my earplugs out and sounds flood in – dogs barking, a gate creaking, women chattering, birds chirping, an airplane soaring, my refrigerator buzzing.

I have to pee, but I beeline for my kitchen instead. I boil water and take the bag of coffee grinds out of the fridge. They’re warm. So is the milk I reach for next. Just last week we had 12 hours of power outages per day; this week it’s up to 16.

I pour my coffee and bring the steaming cup back to my room. Between sips I shower (45 seconds max –the water is ice-cream-headache cold these days), get dressed (jeans, a sweater, a scarf) and shove a spiral notebook and pens into my dusty backpack.

The caffeine kicks in. I open itunes and press play. The acoustic version of “Dr. Jones” comes on. I sing along as I slide on my socks to the kitchen.

I pour the remaining hot water into a bowl and mix in oatmeal, dried apple, walnuts, honey. It tastes just as good as it did yesterday and the day before and the day before. My comfort food.

My morning sustenance. Walnuts, oats, dried applies, honey and COFFEE.

I look at my watch. 8:50. Yikes, I’d better hurry. I shovel spoonfuls of gooey mush into my mouth, slide back across the floor, swallow, shovel more in. I put my laptop and a bag of walnuts in my backpack and zip it up.I lead my bike outside, my eyes squinting as they adjust to the morning light. I take several deep breaths as I pass the begonias in my driveway. They are sweet, sharp. I wish I could bottle the scent.

I turn onto the road. It smells of exhaust and fermented trash but it hardly bothers me anymore. I ignore the piles of banana peels, diapers, chicken bones, unidentifiable brown clump that line the street.

I pass my tomatoes and eggs supplier, a small graying woman who sits behind a crooked wooden stall. Her toothless grin and leathery skin are beautiful in the morning sun, against her bright red scarf. I smile, bow my head and remind myself to ask her name next time I talk to her.

I gather speed – now I’m riding alongside the cars and the three wheeled tuk tuks. I zoom past the arched entrance of the British School, past the cement house that hosts the ‘secret Italian bakery’ and past the Hotel Greenwich Village, whose name I stopped laughing at long ago. I weave around potholes and cows and through packs of street dogs, who seem oblivious to the bustle around them. They are focused on breakfast. Heads down, they wiggle and push their noses through the trash in search of discarded momos, old rice, anything to fill their stomachs.

Landmarks on my ride to work: the British School, Secret Italian Bakery, Hotel Greenwich Village

I reach the office. Bumila, the guard, opens the gate.

Namaste, san chai cha? We each say to each other, exchanging smiles. She takes my bike.

My breath still rapid, I step quickly into the office. I glance at my watch: 9:06. Not bad.

My day begins.

Thursday, November 6, 2008

Election Day

I thought I’d never go to the American Club in Kathmandu. Run by the American Embassy, the three-square block compound looks more like a high security jail than a recreation center. Armed guards line the perimeter and barbed wire coils decorate the three-story high wall. Only Americans are allowed to enter. (If you’re Nepali, tough luck.) According to a friend who’d been, tiled bathrooms, chandeliers, neatly pruned hedges and a grocery store that sells imported organic tahini can be found inside.

It seemed pompous and hopelessly out of touch with its surroundings – a symbol to me of what our country had become. I’ll never go, I thought.

But on election day the Club hosted a party to watch the returns, and I decided to go. I wanted to be amongst “fellow Americans.” I was also secretly excited to see inside, how an ascetic might feel about trying alcohol for the first time.

I expected to feel like an anthropologist – to observe the scene with distance, even distaste, then leave thinking, “OK, I’ve seen it, I’ll never go there again.”

At 7:30 am on November 5, 2008 (or 8:45 pm EST on November 5th) I take a taxi with Sweta, my American colleague, her husband Michael, and my American friend Brendan.

The entrance routine evokes memories from airport security checkpoints – we wait in line; a stern-faced guard flips through our passports then enters them into a database; we walk through a metal detector and a second guard pats us down. Finally, guard number three nods approval and we enter.

Inside, we walk past two clay tennis courts, the American supermarket (large, sterile, without people) and little gold-plated signs with arrows pointing us towards the gym, the sauna and the pool. We find the sign that says “restaurant” and follow it.

The restaurant, where the event is held, smells of pancakes, fancy perfume – and Americans, roughly 50 of them. I haven’t seen this many Americans since my flight from Washington/Dulles four months ago.

At the back of the room, people sit around tables– munching on pancakes and sausages, drinking coffee, half watching the TV in the front of the room, half chatting with one another in rapid American cadence.

A quieter group sits in rows of plastic chairs at the front; their eyes are fixed on the small TV tuned to CNN. They clutch coffee mugs, strain necks towards the TV, speak in low tones to their neighbors, careful not to drown out Anderson Cooper.

Half of the crowd is grey and wrinkled. The old men wear khakis and have bald heads; their wives wear gold earrings and pink lipstick. The other half, the youngsters, wear beards, sandals and beads.

We make our way to the front of the room, walking through the round eating tables. I hear bits of conversations: Do you remember which way Pennsylvania went in the 2004 election? When did you post-mark your absentee ballot? I haven’t had pancakes like these since IHOP!

We watch returns come in from Virginia, Ohio then Pennsylvania. I munch on a cream cheese bagel, the first I’ve had in months. Around me wafts CNN election music, the smell of pancakes and the whispers and shouts of midwest, south and northeast America.

During the commercial breaks, Brendan and I comment on how surprisingly comfortable we feel here. We may be thousands of miles away from the counting and the projecting and the voting that will influence our lives more than we can imagine – but we feel close.

Once in a while, I’m reminded that I’m not home. I see the subtle Newari décor that lines the restaurant ceiling. And as the morning sun creeps into the restaurant and I feel the tea jerk my brain alert, the commentators on TV start to yawn, their eyes droop, the night darkens behind them.

Two hours and ten minutes after we arrive, as I am finishing my second cup of tea, the TV screen projects the most important line of the morning, and quite possibly, of our generation:

“OBAMA ELECTED PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES.”

The moments following are a blur – of cheers, tears, gripping my friend Brendan’s leg, hugging the old man next to me and dancing with Sweta’s husband. I felt the world breath, sigh out, jump up for joy, relief.

I turn around. At least a hundred people are here now, most of them are standing – they’re coming out of hugs, straining to see the TV, pulling handkerchiefs out of their pockets. A young lesbian couple hold hands and stare at the TV with deer-in-the-headlight expressions; a middle-aged man with a scruffy face and a milk jug - sized camera takes pictures of the crowd; a man with grey receding hair takes off his thin spectacles to wipe his tears. The collective emotion in that room was greater than I’d felt. Ever.

As we walk out – past the security guards, through the metal detectors and back into the chaos and soot and color of Kathmandu, I look back at the compound. It looks less ominous, less imposing than it did three hours earlier.

I’d seen a community inside. I’d eaten bagels, chatted about my town in Maine with someone from New Hampshire, exchanged excited glances with strangers after every Obama state victory. And after his national victory, I embraced, danced, cheered and sighed with a roomful of people from my country. I’d felt comfortable. At home, even.

I don’t know that I’ll ever be a regular at the American Club. But I’ll consider going back.

It seemed pompous and hopelessly out of touch with its surroundings – a symbol to me of what our country had become. I’ll never go, I thought.

But on election day the Club hosted a party to watch the returns, and I decided to go. I wanted to be amongst “fellow Americans.” I was also secretly excited to see inside, how an ascetic might feel about trying alcohol for the first time.

I expected to feel like an anthropologist – to observe the scene with distance, even distaste, then leave thinking, “OK, I’ve seen it, I’ll never go there again.”

* * *

At 7:30 am on November 5, 2008 (or 8:45 pm EST on November 5th) I take a taxi with Sweta, my American colleague, her husband Michael, and my American friend Brendan.

The entrance routine evokes memories from airport security checkpoints – we wait in line; a stern-faced guard flips through our passports then enters them into a database; we walk through a metal detector and a second guard pats us down. Finally, guard number three nods approval and we enter.

Inside, we walk past two clay tennis courts, the American supermarket (large, sterile, without people) and little gold-plated signs with arrows pointing us towards the gym, the sauna and the pool. We find the sign that says “restaurant” and follow it.

The restaurant, where the event is held, smells of pancakes, fancy perfume – and Americans, roughly 50 of them. I haven’t seen this many Americans since my flight from Washington/Dulles four months ago.

At the back of the room, people sit around tables– munching on pancakes and sausages, drinking coffee, half watching the TV in the front of the room, half chatting with one another in rapid American cadence.

A quieter group sits in rows of plastic chairs at the front; their eyes are fixed on the small TV tuned to CNN. They clutch coffee mugs, strain necks towards the TV, speak in low tones to their neighbors, careful not to drown out Anderson Cooper.

Half of the crowd is grey and wrinkled. The old men wear khakis and have bald heads; their wives wear gold earrings and pink lipstick. The other half, the youngsters, wear beards, sandals and beads.

We make our way to the front of the room, walking through the round eating tables. I hear bits of conversations: Do you remember which way Pennsylvania went in the 2004 election? When did you post-mark your absentee ballot? I haven’t had pancakes like these since IHOP!

We watch returns come in from Virginia, Ohio then Pennsylvania. I munch on a cream cheese bagel, the first I’ve had in months. Around me wafts CNN election music, the smell of pancakes and the whispers and shouts of midwest, south and northeast America.

During the commercial breaks, Brendan and I comment on how surprisingly comfortable we feel here. We may be thousands of miles away from the counting and the projecting and the voting that will influence our lives more than we can imagine – but we feel close.

Once in a while, I’m reminded that I’m not home. I see the subtle Newari décor that lines the restaurant ceiling. And as the morning sun creeps into the restaurant and I feel the tea jerk my brain alert, the commentators on TV start to yawn, their eyes droop, the night darkens behind them.

Two hours and ten minutes after we arrive, as I am finishing my second cup of tea, the TV screen projects the most important line of the morning, and quite possibly, of our generation:

“OBAMA ELECTED PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES.”

The moments following are a blur – of cheers, tears, gripping my friend Brendan’s leg, hugging the old man next to me and dancing with Sweta’s husband. I felt the world breath, sigh out, jump up for joy, relief.

The minute Obama was elected. Fist pumps and tears all around.

Minutes after. Sweta (grey shirt clapping), her husband Michael (blue shirt and victory fist), Brendan (plaid red shirt, pensive look), me (black zip-up)

This picture says it all. Michael.

Minutes after. Sweta (grey shirt clapping), her husband Michael (blue shirt and victory fist), Brendan (plaid red shirt, pensive look), me (black zip-up)

This picture says it all. Michael.

I turn around. At least a hundred people are here now, most of them are standing – they’re coming out of hugs, straining to see the TV, pulling handkerchiefs out of their pockets. A young lesbian couple hold hands and stare at the TV with deer-in-the-headlight expressions; a middle-aged man with a scruffy face and a milk jug - sized camera takes pictures of the crowd; a man with grey receding hair takes off his thin spectacles to wipe his tears. The collective emotion in that room was greater than I’d felt. Ever.

Michael and Sweta embrace. Two months ago they had their first child, a baby girl.

As we walk out – past the security guards, through the metal detectors and back into the chaos and soot and color of Kathmandu, I look back at the compound. It looks less ominous, less imposing than it did three hours earlier.

I’d seen a community inside. I’d eaten bagels, chatted about my town in Maine with someone from New Hampshire, exchanged excited glances with strangers after every Obama state victory. And after his national victory, I embraced, danced, cheered and sighed with a roomful of people from my country. I’d felt comfortable. At home, even.

I don’t know that I’ll ever be a regular at the American Club. But I’ll consider going back.

Monday, November 3, 2008

Nepal-oween

The night started out on track...

Nepali institutions meet: a teeka (the red dot Hindus put on their foreheads), Dal Bat (the quintessential Nepali dish of rice and lentils) and ‘load shedding’ (ie power outages - there’s not enough electricity for everyone in Kathmandu so authorities cut power ~30 hours a week in each neighborhood.)

(Fittingly he was thrown into the dump the next day.)

…I fell into a manhole!?!!!

Getting out was tricky. Uncontrollable giggles prevented my muscles from working. The two friends with me were useless, too – they hovered above laughing, crying (from laughing) and taking pictures. It took a good 5 minutes to calm down and pull me out. (Five minutes flies by when I'm cleaning up the table from dinner or catching up on email. It slowed to a blurry halt that night!!!)

"The incident" left me with a French-baguette-sized bruise on my shin, mysterious slime on my red pjs (which I’d planned to return the next day) and… a fun story.

Nepali institutions meet: a teeka (the red dot Hindus put on their foreheads), Dal Bat (the quintessential Nepali dish of rice and lentils) and ‘load shedding’ (ie power outages - there’s not enough electricity for everyone in Kathmandu so authorities cut power ~30 hours a week in each neighborhood.)

...and stayed that way for most of the night.

Smiles! Costumes! Fun!

John McCain even made an appearance.

(Fittingly he was thrown into the dump the next day.)

Then, at the end of the night things got weird. I was walking home and…

This is me trying. Halfway out.

…I fell into a manhole!?!!!

Getting out was tricky. Uncontrollable giggles prevented my muscles from working. The two friends with me were useless, too – they hovered above laughing, crying (from laughing) and taking pictures. It took a good 5 minutes to calm down and pull me out. (Five minutes flies by when I'm cleaning up the table from dinner or catching up on email. It slowed to a blurry halt that night!!!)

"The incident" left me with a French-baguette-sized bruise on my shin, mysterious slime on my red pjs (which I’d planned to return the next day) and… a fun story.

Saturday, November 1, 2008

Home

This post has nothing to do with Kathmandu. But everything to do with what's been on my mind lately.

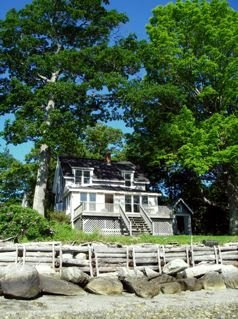

My childhood home was sold last week.

In some ways, it’s easier to be far away. I am not facing the boxes and the empty house. I didn’t have to meet the new owners. I didn’t see my room without the faded sunflower-shaped collage that’s been on its wall since before I can remember.

But it’s also harder, perhaps for the same reasons. I'm far away and I’m not forced to think about it. So when I do, the feelings are sharp.

Thoughts of home seeped into my consciousness at unexpected, often unwelcome times this week:

Why do I care so much about this move? “Home is where the heart is,” right? Why is this physical place – really just four walls and a roof – so important? A few reasons come to mind:

As these questions float in my mind this week, I read an email from the IRC. The headline: “IRC suspends programs in North Kivu, Congo, following renewed fighting.” It goes on to say that approximately 36,000 people have been recently displaced from their homes. I follow the link to read another article, this one by a reporter who traveled to formerly war-torn Western Congo. The family he stayed with the first night –poor and war affected – insisted on offering him rice and sardines. The man's wife had given birth to a daughter by a C-section earlier that day.

Then I think of Mary, a Liberian woman I met in Ghana who’s lived a third of her life in a refugee camp. She sells donuts for a living and raises her fatherless grand daughter, Lisa, in their little cement house. She keeps a garden in a dirt patch next to their house.

Their stories put my home-aches in perspective. And remind me that humans are good at adapting. Those who survive the current fighting in Congo will continue to gather firewood, to nurse their children and to seek work after the conflict is over. And Mary is still planting flowers and sending her grandchild to school.

I will adapt.

My childhood home was sold last week.

In some ways, it’s easier to be far away. I am not facing the boxes and the empty house. I didn’t have to meet the new owners. I didn’t see my room without the faded sunflower-shaped collage that’s been on its wall since before I can remember.

But it’s also harder, perhaps for the same reasons. I'm far away and I’m not forced to think about it. So when I do, the feelings are sharp.

Thoughts of home seeped into my consciousness at unexpected, often unwelcome times this week:

- While cleaning my room. Yesterday the song “Ghetto Superstar” came on as I cleaned my room. It brought me to 14 Ocean Street, sometime in the late 90s. My best friend Maya and I are in my bedroom. We’re wearing flared jeans and t-shirts from the Gap. We hold hairbrush microphones, squint our eyes and dance around my room, careful not to bonk our heads on my loft bed.

- While voting. I tear up when I fill in my absentee ballot. They ask for my address in The States. I don’t know what to put.

- While Skype-ing. My parents have stress and weariness in their voice each time we’ve talked recently. 25 years of stuff to get rid of, to sort through, to throw out and to pack up. It wears.

- While uploading pictures. As I upload my latest pictures into iphoto, I see the folder labeled “Home.” It feels masochistic to click on it but I do anyway. I tear up at the first picture: its a view of the sunrise from our deck - reds, oranges and pinks mirrored in the still morning water. The nostalgia builds as I scroll through the rest – dad sitting on the porch with a cup of coffee in his hand, a book in his lap; my family and the Loxtercamp/McGuires around our dining room table, celebrating one the what-feels-like-hundreds of birthdays we've shared together (the staple cake with Ben & Jerry's, party hats and goofy smiles present); Max sleeping in dad’s puffy chair in ‘the boat shed.’

Why do I care so much about this move? “Home is where the heart is,” right? Why is this physical place – really just four walls and a roof – so important? A few reasons come to mind:

- Home provided stability. My life is transient at the moment – I’m living in Nepal, but who knows where I’ll be in eight months; I’m working for an NGO, but I don’t know if it’s what I want to “do” when I “grow up;” I have friends here, but my closest and oldest friends are scattered about The States. Home countered all this flux. If I ever felt lonely or lost, I could come home to our fireplace, to my baby blanket, to pancake breakfasts on our porch. I could come home and find Colonel Bruce next door on his porch, ready with a virgin Shirley Temple and a story from ‘back in Korea.’ “My surrogate granddaughter!” he’d say as I walk across our adjoining lawn. My home represented security, stability, comfort. Now where to run if things get tough?

- Home provided identity. “I am a Mainer” and “I am from Belfast” are phrases I’ve been saying since I could speak. They are as automatic and engrained as “My name is Rosie.” I also feel proud saying them. I met a lot of people in college who grew up in the suburbs of New Jersey or in high-rise buildings of Manhattan; I felt unique to be from a small town, from a community, from a place where everyone is connected. A place where my third grade teacher is also my mom’s best friend; where my next-door neighbor was a City Council member and taught my middle school-band class how to march; where my doctor is also the owner of the local diner where I go for pancakes on Saturdays. Belfast and its people shaped me. If Belfast, Maine is no longer my home, who am I? Am I now someone who simply grew up in Maine? As McCain has done so much this past month, I’ll have to change “my narrative.” That feels about as hard as changing my name – maybe harder.

- Home represents innocence, childhood. My freshest memories of home are these: racing barefoot along the hot beach rocks with summer-friend Paige, telling secrets with Maya under a sheet-fort in my living room, sipping hot cocoa and munching cookies by the fire after an afternoon of snowman-making, running inside the house dripping wet, pulse racing, after a morning of collecting crabs, swimming to the dock and making floating inner tube towers on the beach, and on and on… My memory is certainly rose-colored, tinged by nostalgia. But it is what it is. At my most melodramatic, it feels like I’ve lost not just the house, but my youth too.

As these questions float in my mind this week, I read an email from the IRC. The headline: “IRC suspends programs in North Kivu, Congo, following renewed fighting.” It goes on to say that approximately 36,000 people have been recently displaced from their homes. I follow the link to read another article, this one by a reporter who traveled to formerly war-torn Western Congo. The family he stayed with the first night –poor and war affected – insisted on offering him rice and sardines. The man's wife had given birth to a daughter by a C-section earlier that day.

Then I think of Mary, a Liberian woman I met in Ghana who’s lived a third of her life in a refugee camp. She sells donuts for a living and raises her fatherless grand daughter, Lisa, in their little cement house. She keeps a garden in a dirt patch next to their house.

Their stories put my home-aches in perspective. And remind me that humans are good at adapting. Those who survive the current fighting in Congo will continue to gather firewood, to nurse their children and to seek work after the conflict is over. And Mary is still planting flowers and sending her grandchild to school.

I will adapt.

Ode to 14 Ocean St.

Both self-indulgent and therapeutic, I've documented home, the way I remember it. This is 14 Ocean Street:

The Smells

Mostly, it smells like dog and pine. At dinnertime though, garlic and onion wafts from the kitchen. During the winter, it smells like wood smoke and the pine smell intensifies. When Bern Porter (old eccentric poet) comes to visit, the whole house smells like old un-showered man and old cabbage. We open the windows and doors after he leaves. When the cats or Max are getting their monthly flea treatments, an unpleasant chemical smell lingers. In the summer, the breeze from the ocean carries in smells of seaweed and salt water. Also grass clippings. Summer evenings, the smell of Colonol Bruce’s barbeque seeps in our windows and screen doors. Max disappears. Occasionally, when Max rolls in something on the beach, the house smells of dead seal or rotten fish.

The Sounds

Before dinner, NPR plays loud from the kitchen – I hear the familiar jingle (doo doo dooo) and then, “This is all things considered, I’m Alex Seigel.” The sizzle of onions and mushrooms sautéing fills the quiet moments between segments.

In the mornings, I hear coffee perking; dad clicking at his computer; Max’s toenails tap on the wood floors.

During the day, I hear the “shake-shake” of Max’s kibbles as he pushes them around in his bowl. I hear the phone ring and ring – no one gets up to answer it.

In the summer, I hear a lawnmower most days (Dick and Bruce obsess and compete over their pruned lawns.) I hear a boat engine; sea gulls cawing; kids laughing on the beach; Max barking at them. I hear “NUMBER 42, YOUR ORDER IS READY,” the muffled woman’s voice broadcast from the Lobster Pound Restaurant across the bay. During the Bay Festival every July, I hear rock music, the clank of metal and girls screaming from down the beach.

In the winter, I hear logs drop as dad piles wood next to the fireplace; I hear the click-click-click as our heat comes on, the hot water filling up the cold pipes. Some nights I hear howling wind and waves crashing outside.

The Sights

Delicious rainbow. Our dock. Big boat that's parked there every summer. Sigh.

The Smells

Mostly, it smells like dog and pine. At dinnertime though, garlic and onion wafts from the kitchen. During the winter, it smells like wood smoke and the pine smell intensifies. When Bern Porter (old eccentric poet) comes to visit, the whole house smells like old un-showered man and old cabbage. We open the windows and doors after he leaves. When the cats or Max are getting their monthly flea treatments, an unpleasant chemical smell lingers. In the summer, the breeze from the ocean carries in smells of seaweed and salt water. Also grass clippings. Summer evenings, the smell of Colonol Bruce’s barbeque seeps in our windows and screen doors. Max disappears. Occasionally, when Max rolls in something on the beach, the house smells of dead seal or rotten fish.

The Sounds

Before dinner, NPR plays loud from the kitchen – I hear the familiar jingle (doo doo dooo) and then, “This is all things considered, I’m Alex Seigel.” The sizzle of onions and mushrooms sautéing fills the quiet moments between segments.

In the mornings, I hear coffee perking; dad clicking at his computer; Max’s toenails tap on the wood floors.

During the day, I hear the “shake-shake” of Max’s kibbles as he pushes them around in his bowl. I hear the phone ring and ring – no one gets up to answer it.

In the summer, I hear a lawnmower most days (Dick and Bruce obsess and compete over their pruned lawns.) I hear a boat engine; sea gulls cawing; kids laughing on the beach; Max barking at them. I hear “NUMBER 42, YOUR ORDER IS READY,” the muffled woman’s voice broadcast from the Lobster Pound Restaurant across the bay. During the Bay Festival every July, I hear rock music, the clank of metal and girls screaming from down the beach.

In the winter, I hear logs drop as dad piles wood next to the fireplace; I hear the click-click-click as our heat comes on, the hot water filling up the cold pipes. Some nights I hear howling wind and waves crashing outside.

The Sights

Delicious rainbow. Our dock. Big boat that's parked there every summer. Sigh.

Goodbye.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)